The hidden cost of cashback: How shopping extensions track you—and how to limit it

I have acquaintances who talk excitedly about cashback sites for shopping—and I get the appeal. Why not get money back if you’re already going to be buying those things anyway? But I’m the one who replies, “Have you looked into what they do with your data?”

(I am very fun to chat with at parties.)

Here’s the thing: Cashback sites can be useful, so long as you’re smart about how you use them. What websites know about you can make life harder in the wrong circumstances.

Table of Contents

What is a cashback site?

Cashback websites work like this: You install an extension on your browser (or an app on your phone), then start shopping. As you visit online stores, notifications will appear when an offer is available—either a percentage (often capped at a certain amount) or a fixed dollar reward. Major cashback sites include Rakuten (formerly Ebates), Swagbucks, and TopCashBack.

During peak shopping periods like Black Friday and Cyber Monday, some incentives can jump up considerably. For example, during Cyber Monday, cashback reached as high as 15 percent for some shops. Spend even $50 to $100, and that starts to add up. (At the very least, it covers sales tax and a little extra for most people.)

Similar (but still different) are cashback offers through banks, often tied to a credit card. You activate the offer through your bank’s site or app first. Then when a charge to your credit card matches an active offer, you automatically get a partial refund applied, according to the terms (e.g., 2 percent back, up to $5). Sometimes these can be pretty sizable—like $100 off a $500 or more purchase at Dell. The offers cycle regularly, with set expiration dates. You also must activate them first before they apply—they won’t count retroactively.

Rakuten

The main difference between cashback site and cashback offers is that a cashback site monitors all of your online shopping activity. Have a look at some of the information collected by Rakuten, which is defined in its privacy policy:

“…records of products, product types, merchants, merchant types, goods or services purchased, obtained, or considered by you, including products, merchants and coupons you searched for, viewed or clicked, items added to cart and abandoned, shopping trips initiated, merchant sites visited from our Services, transaction history related to our Services, purchase confirmation data…”

The rest of Rakuten’s policy defines multiple other categories of captured data, including the URLs of pages you visit, timestamps of when you’re browsing, and the last page that you were on before you arrived at Rakuten’s site. Rakuten also clearly says it makes assumptions about your likely preferences, interests, and behavior, as permitted by law.

Why? Rakuten says it won’t sell your data to third parties, but unless you opt out, it can (and will) share your data with third-parties. It also has a vested interest in understanding how you tick, so that it can better entice you to shop….even when you perhaps don’t intend to.

Bank of America

As for cashback offers, they are more limited in the information your bank ends up with. The bank sees the transaction, and then automatically applies your reward. But that’s not extra data the company is receiving—it already would know where and when you’re shopping based on the charges. And your bank is already profiling you, in part to help combat fraudulent charges and activity if it happens to your account.

Your bank can (and will) share its data with third-party affiliates both to provide service and to allow those outside businesses to market to you. You can however opt out of such data sharing (which I recommend).

So what’s the problem with cashback sites having my data?

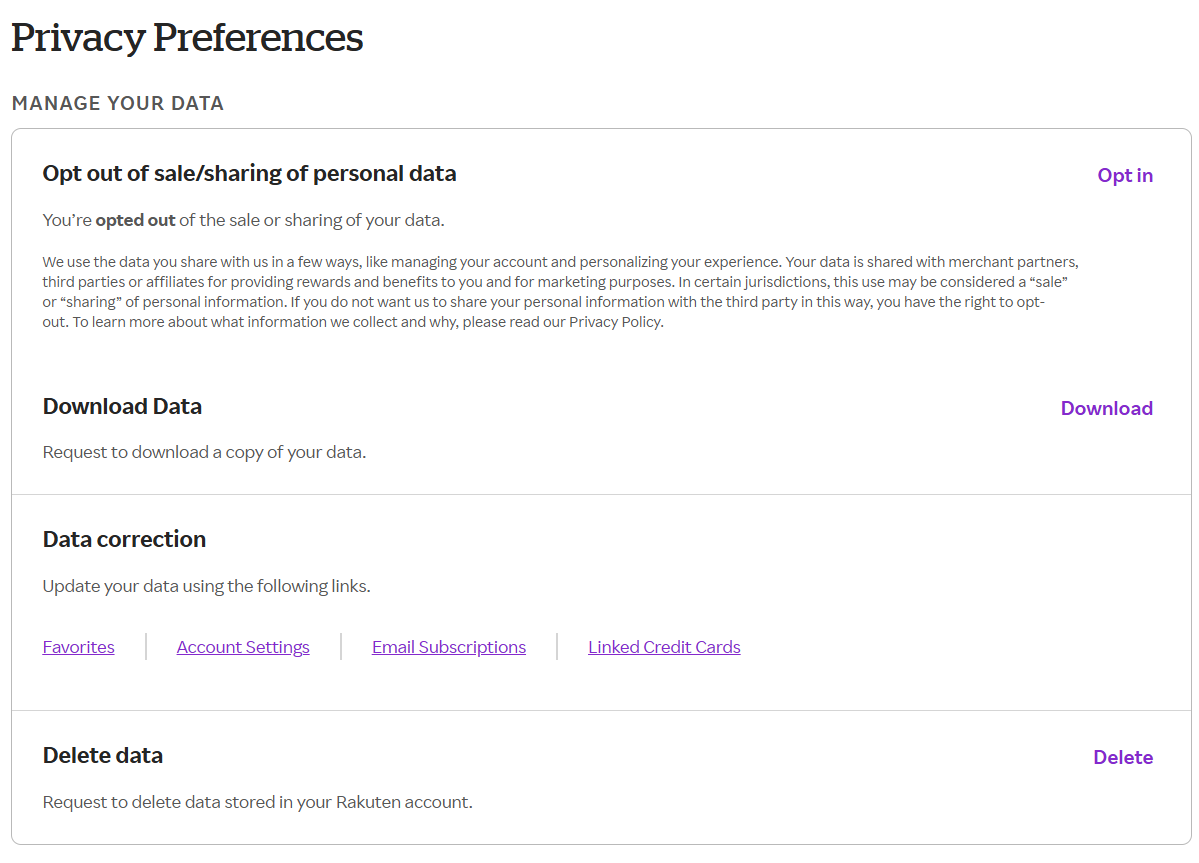

As an exercise, I started a Rakuten account, did a little navigating, and made a couple of small purchases. Then I made a data request to see what sort of information they captured from me.

It’s nothing particularly shocking, if you’re already familiar with Rakuten’s privacy policy. I definitely saw data on the sites that I visited and the times, the products I bought, info on the device and browser I used, and the like.

Rakuten

There’s a lot of data, most of which seems harmless. But let’s not forget: We’re now in the era of websites easily hacked, and personal data leaked. That info stays on the internet forever. And shopping data contains a lot of seemingly mundane but still personal information about you—and now a cashback site is collecting all of this in one, convenient place.

That information could be used to craft personalized attacks—think scams via phishing or even extortion, if a bad actor thinks you might be susceptible to certain kinds of scams or could be embarrassed by public disclosure of your shopping habits.

Should I stop using cashback sites and cashback offers?

The short answer is no, though some individuals may find their privacy is worth forgoing a little cashback. However, I recommend being savvy about how you use them.

My personal take is that I can’t predict the future, so the less personal data that could leak, the better. Twenty years ago, I didn’t imagine we could connect online as fast as we do now, much less extrapolate tiny details about strangers through just a little bit of information. (The groups of folks who can identify a location just from a handful of clues in a photo are both wildly impressive and definitely unnerving.)

So I would:

- Choose sites that clearly state what information they collect and how they use it. Avoid ones that sell your data to third parties.

- Create and use passkeys for as many shopping sites as possible. (Really, all sites that offer them.) These can’t be phished, so if there ever is a leak of your shopping data and you start getting hit by phishing emails, you have a much lower chance of caught off-guard by a bad email or message.

- Limit your cashback purchasing activity to a separate browser—and only use that browser when you’re ready to make the purchase. This minimizes the information that a cashback site can collect about your browsing habits.

(Speaking of great alternative browsers—when I poking around at cashback sites, I used Vivaldi. It’s well-regarded by my colleagues Mark Hachman and Michael Crider and I now can say I get why they like it.)

Times are tough economically, and the forecasts imply it could be harder this coming year. (I hope not, but…) So cashback makes sense. Just ensure it makes sense for your long-term online safety, too.